Adapters and Config: Multi-database Support in Harlequin

When I released Harlequin v1.0 at the end of September, I was surprised and excited by the response. I knew I had created something that I wanted to use, but it was amazing to see how many others were interested: Harlequin was submitted to Hacker News, where it quickly shot to #2 on the Front Page. The Harlequin repo gained hundreds of stars overnight, and thousands of people downloaded the package over the next week.

But I got some feedback on Hacker News and in a GitHub issue that made me realize Harlequin could be much bigger: why only DuckDB? Why not support any database?

Well, today, just two months later, it does. Harlequin is a SQL IDE for any database, not just DuckDB.

In this post, I’m going to cover the new features since v1.0 and highlight some of the code and libraries that make it possible.

Adapter Plug-ins

Harlequin’s database interface has been abstracted into something I call an Adapter, which can be loaded as a plug-in. Harlequin now ships with two adapters, DuckDB and SQLite, and others can be pip-installed, either as Harlequin extras (e.g., pip install harlequin[postgres]) or independent packages (pip install harlequin-postgres). You select an adapter when you launch Harlequin:

$ harlequin -a sqliteAdapters each register their own CLI options; for example, after installing the Postgres adapter, Harlequin will accept -h, -p, and other Postgres-specific config:

$ harlequin -a postgres -h localhost -p 5432 -U admin --password my-secret -d postgresYou can use harlequin --help to view all available options (more on this below).

Adapters are only 200-300 lines of code, plus another ~200 lines of code-as-config to define options. That’s pretty lightweight! I found I can write one for a database I know in a couple of hours. I wrote a guide for writing adapters, and created a template repo to make it as easy as possible. Right now only the DuckDB, SQLite, and Postgres adapters are complete, but more are expected soon from the community. If you would like to create an adapter, please reach out!

Config Files and Profiles

Adapters create a new problem — those connection strings are long and there are too many options to remember and type every time at the command line. Enter config files and profiles.

Now you can define Harlequin config in a TOML file:

default_profile = "duck-f1"

[profiles.duck-f1]

adapter = "duckdb"

conn_str = ["~/f1.db"]

init_path = "~/.duckdbrc"

[profiles.local-pg]

theme = "native"

limit = 10_000

adapter = "postgres"

host = "localhost"

user = "postgres"

password = "my-secret"

database = "postgres"

port = 5432Now simply running harlequin will use the DuckDB adapter to connect to the ~/f1.db file, and harlequin -P "local-pg" will connect to a Postgres database at localhost, with a different theme and lower row limit!

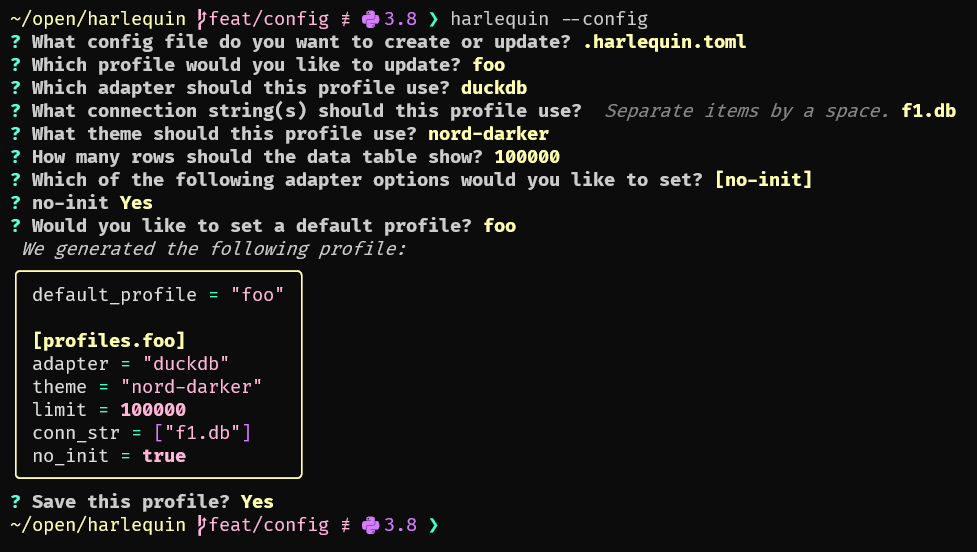

But there’s more… creating a config file by hand is slow and error-prone, so Harlequin now ships with a tool to create and update config files for you. Simply run harlequin --config and the config wizard will walk you through all of the available options for Harlequin and your selected adapter. After you finish, it looks like this:

Harlequin will load config from .harlequin.toml or pyproject.toml files; if Harlequin finds multiple config files, it merges them, with the files in the current working directory superseding those in your home directory.

How it Works

I learned a lot developing this set of features for Harlequin. Here are a few of the niftier solutions to the problems I encountered along the way.

Plug-in Discovery

This is actually pretty standard and easy, but I didn’t find a simple walkthrough. So here it is.

First, a package has to declare an entry point in a specific group, using its packaging software. For a project that uses uv, that looks like these two lines in the project’s pyproject.toml file:

[project.entry-points."harlequin.adapter"]

my-adapter = "my_package_name:MyAdapter"After installing that package, an entry point named my-adapter is discoverable to any Python program. You can use the entry_points function in importlib.metadata to do this. Except that the API for entry_points changed in Python 3.10, so if you’re running an older Python, you’ll need to install the backport, importlib_metadata.

import sys

if sys.version_info < (3, 10):

from importlib_metadata import entry_points

else:

from importlib.metadata import entry_points

adapter_eps = entry_points(group="harlequin.adapter")entry_points returns an EntryPoints object, which supports both __getitem__ and __iter__, so you can grab a specific EntryPoint with adapter_eps["my-adapter"] or you can iterate over the collection.

An EntryPoint object has a name property and a load() method; load() returns the Python class defined by the plugin (e.g., MyAdapter); I use these to build a mapping of plugin names to their Python classes. Essentially:

adapters = {ep.name: ep.load() for ep in adapter_eps}Harlequin builds this mapping as the very first step after you run harlequin, which allows us to do the next things.

Dynamic Options

Harlequin uses Click for its command-line argument parsing. Click provides a nice API based on decorators to create a command from a Python function and add options. Typically that would look like this:

import click

@click.command

@click.option(

"--my-option",

"-m",

help="My very special option."

)

def my_command(my_option: str) -> None:

...There are many types of options, like flags, path options, choice options, etc. I wanted adapters to be able to declare their own options, which Harlequin could parse and pass into their invocation. This allows, for example, the Postgres adapter to define a --port option. Doing this dynamically required a few steps.

First, I created an abstraction that would allow Adapters to define options without knowing anything about Click (this also allows us to reuse this concept of an Option for other features, like the Export UI and Config Wizard). A simplified version of the TextOption is a dataclass:

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class TextOption:

name: str,

description: str

short_decls: list[str] | None,The real implementation has a few other bells and whistles, but you get the point.

Adapters have a class variable called ADAPTER_OPTIONS that is a list of options:

class MyAdapter(HarlequinAdapter):

ADAPTER_OPTIONS = [

TextOption(

"my-option",

short_decls=["-m"],

description="My very special option."

),

]Next, it’s important to understand that a decorator is a callable, and the decorator syntax is just shorthand for wrapping a callable in another callable. From our click example above, we could do this instead:

my_command = click.option("--my-option", "-m", help="...")(my_command)

my_command = click.command()(my_command)As a consequence, you can call click.option() at any time, and then later pass your command to the returned callable. So the TextOption class defines a to_click method, that returns a Click Option callable:

class TextOption:

...

def to_click() -> Callable[[click.Command], click.Command]:

return click.option(

f"--{self.name}",

*self.short_decls,

help=self.description,

)Putting it together, when you type harlequin at the command line, Harlequin iterates over the installed adapters, then iterates over each option, and builds its own CLI command, at run-time. Essentially:

def build_cli() -> click.Command:

adapters = load_plugins() # as above

fn = launch_harlequin

for adapter_cls in adapters.values():

for option in adapter_cls.ADAPTER_OPTIONS:

fn = option.to_click()(fn)

return fn

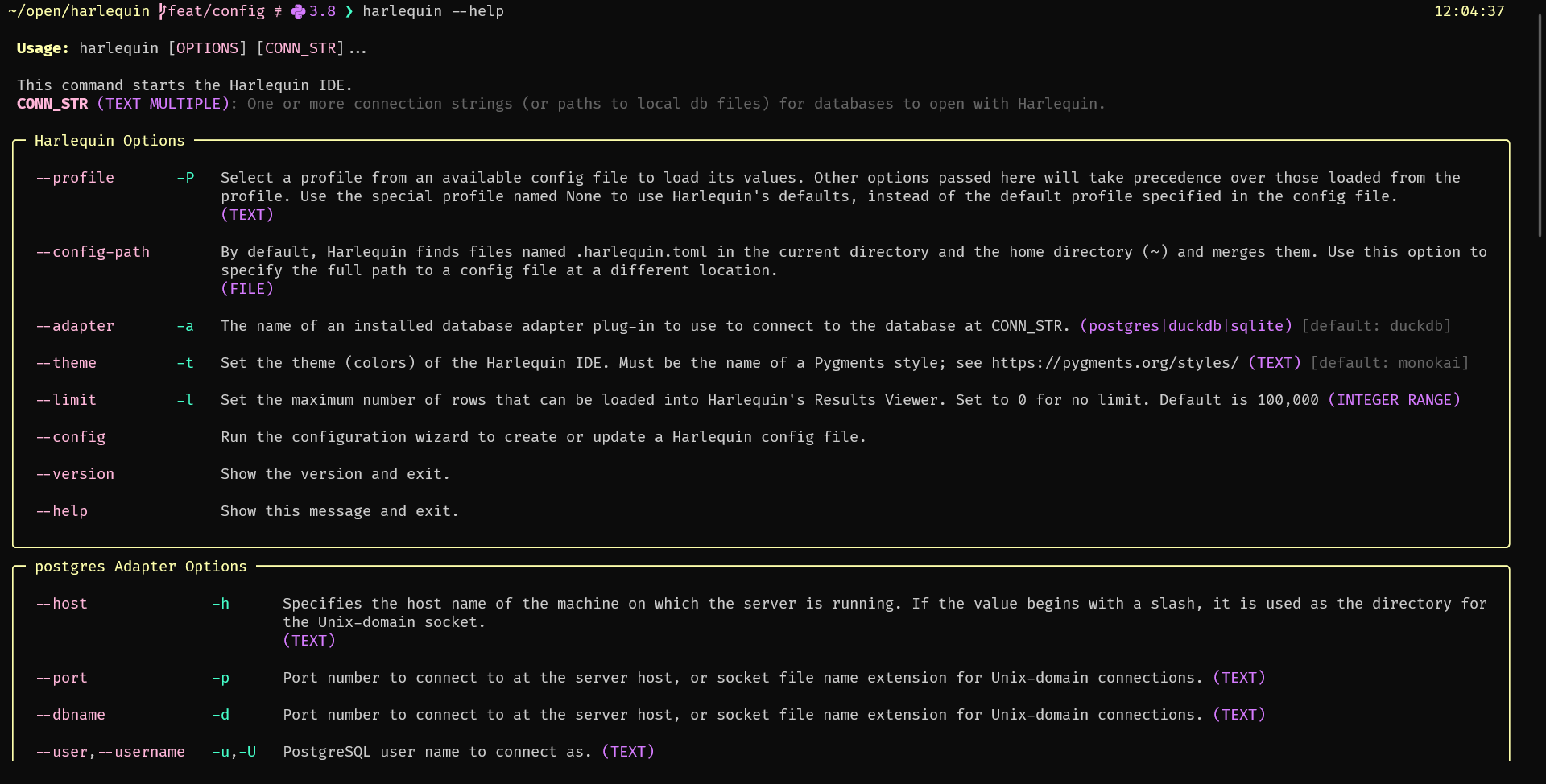

build_cli()()A Beautiful Help Option

Click provides a default --help option that lists all commands and options, along with their descriptions. It’s generated automatically (even with the dynamic methods above) and will look familiar to CLI users, but with multiple adapters installed, there were so many options that it was hard to read the Harlequin help.

rich-click is a new project that patches Click’s default help option and provides prettier output. Critically for Harlequin, it allows you to group options together under a named panel. We build these groups when iterating through each adapter’s ADAPTER_OPTIONS. The result is amazing:

Config Wizard

Config files are fine for advanced users, but I wanted a tool that would help everyone discover the config options for their adapter and help them set the right values.

From the beginning, I envisioned a set of CLI prompts for this, and found Questionary to have the features I needed (I realized way too late that this could have been another Textual app — Harlequin is a Textual app — but that’s a story for another day).

Questionary makes it easy enough to create prompts for things like simple text, paths, and choices. It also provides tools for styling and validating input. For example, the first prompt asks for the config file we’re creating or modifying, providing autocomplete and validation:

raw_path: str = questionary.path(

"What config file do you want to create or update?",

default=".harlequin.toml",

validate=lambda p: True

if p.endswith(".toml")

else "Must have a .toml extension",

style=HARLEQUIN_QUESTIONARY_STYLE,

).unsafe_ask()One unexpected wrinkle is that Python’s built-in tomllib doesn’t provide a way to write TOML files, only read them. The PEP gives reasons, but idk. Anyway, there is a great, format-and-comment-preserving library for writing TOML called tomlkit. It was very easy to swap in for tomllib, since the TOMLDocument class acts just like a dictionary.

Try it out

Thanks for reading. If you haven’t already tried Harlequin, give it a spin! Read the docs or just shoot from the hip:

$ pipx install harlequin